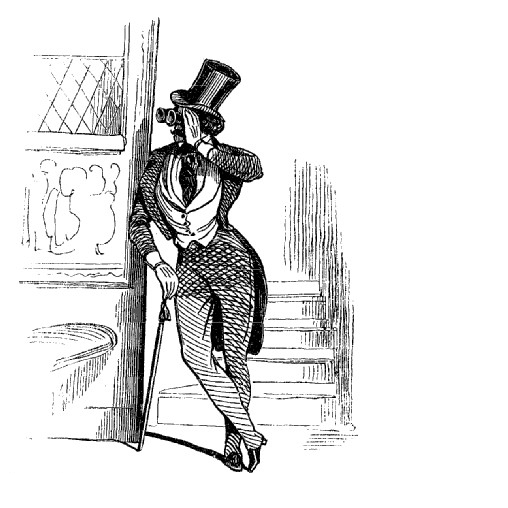

Louis Huart’s Physiologie du Flâneur (1841) is a pop satire of the aimless streetwalker. The journalist catalogs the variations of the flâneur: his habits and his follies. The book is lovingly illustrated with sarcastic prints by Thèodore Maurisset, Marie-Alexandre Alophe, and the esteemed Honoré Daumier.

A selection of illustrations are reproduced below, sourced from Gallica, the digital library of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The illustrations are not individually credited in the original book.

“Cruising Modernity” is the second chapter of Mark W. Turner’s Backward Glances: Cruising Queer Streets in London and New York (London: Reaktion Books, 2004), and it works as a stand-alone essay comparing and contrasting 19th-Century definitions of the flâneur with those of the 20th-Century cruiser, expanding their cohabitation of the modern urban realm. Along the way, Turner employs the imagery of Huart’s Physiolgie in order to pin down the image of the flâneur.

In order to further confuse the distinction, the images below are captioned not with Huart’s original accompanying text, but rather with select excerpts from Turner’s essay. This way, we can more impressionistically merge the image and the MO of the two, expanding our modernity as well.

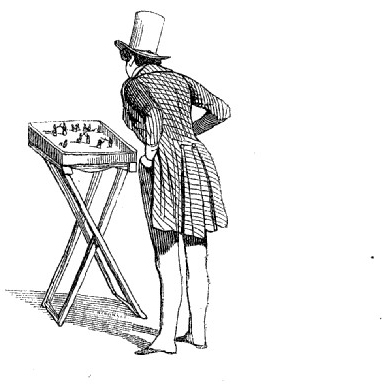

“As the Physiologie describes him, the flâneur is someone with the air of doing nothing, completely at ease, untroubled by the world around him. And he loves to look.” (p62)

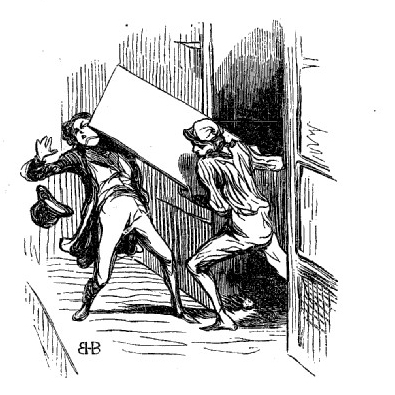

“Cruising is a practice that exploits the ambivalence of the modern city.” (p46)

“In fact, it is precisely because of this uncertainty in the streets withs its many kinds of strollers that our cruisers are able to wander (or window shop).” (p54)

“[He brings] together illicit assignations, sexual transgression, masquerade and men passing on the streets; he locates himself on a hitherto little-known map of the city.” (p49)

“Who or what is he looking at? We don’t know much, but we can guess that he wants to be noticed – he leans nonchalantly.” (p66)

“The text never fully unveils the secrets of the nights, and the mystery of these street-walking men remains a coded mystery of the city itself.” (p55)

“Even in the wry account, it is not so much the physical attributes that matter […] so much as the urban manner, the way of inhabiting the streets.” (p64)

“Yet the cruiser and the flâneur are not that far apart – both with leisure time, a bit money in their pockets, imagination, good taste and, especially, ‘freedom of action.’” (p64)

“It is important to emphasize, as Bech does, that cruising is a process of walking, gazing, and engaging another (or others), and it is not necessarily about sexual contact.” (p60)

“What I want to emphasize is the need to explore the meanings of their urban movement, rather than speculating about a specific sex act this is never offered, and to accept their contingency as agents walking the city.” (p56)

“For Simmel, the mutual exchange of the passing glance – that contingent, fleeting, Baudelairean moment – can be a vital point of interaction, an expression of togetherness rather than of alienation, of connection rather than separation.” (p59)

“They even express desire and longing: but still a fundamental uncertainty and ambiguous understanding of their relationship to the urban environment remains.” (p56)

Physiologie du Flâneur / Louis Huart, with illustrations by Honoré Daumier, Thèodore Maurisset, and Marie-Alexandre Alophe) / Paris / 1841

&

“Cruising Modernity” / Mark W. Turner / 2004