Scene: 1983

In Architectural Record’’s first ‘Record Interiors’ issue (September, 1983), a roundtable of architects, interior designers, and developers have a tedious discussion about the line between ‘architecture’ and ‘interior.’ Perhaps the only insightful interaction is between Greg Landahl and Stanley Tigerman. Landahl – who would later become a celebrated interior designer, claiming that title – is initially identified as an architect “whose firm has done mostly interiors work.” Tigerman – member of the Chicago Seven – was already an established PoMo icon. The two agree that in 1983 it’s fashionable for architects to focus on interiors.

Landahl: “The crux of the issue from the architectural education viewpoint is that interiors are now fashionable, current, being talked about. Ten years ago when I graduated from school, buildings were important, interiors weren’t. Now that interiors are important, people are going to talk about whether interior design is objective or subjective, pretty or ugly, a separate discipline or a part of total design. Ten years ago, at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, if they wanted to bury you somewhere, they buried you in interiors. I got buried in interiors, and found I liked it.”

Tigerman: “Landhal has brought up fascinating ideas – some essential things about the different characters at this table. What I think I hear him say is that taste has come out of the closet; that while some years ago it wasn’t fashionable to talk about taste (which is why architects looked down on interior decorators), it now is not just fashionable but very important, not just in interiors but in the design of exteriors. It will be interesting to see the effect of the work of Michael Graves and others in the context of the more pragmatic things that deal with structuring of interiors. Interiors have always been important and legitimate; but they were long frowned on by architects because they dealt with taste. That made architecture a bit hermetic and a bit private. But that has changed.”

Tigerman (L) and Landahl (R) as photographed at the roundtable (Architectural Record, Sept. 1983)

Scene: 1990

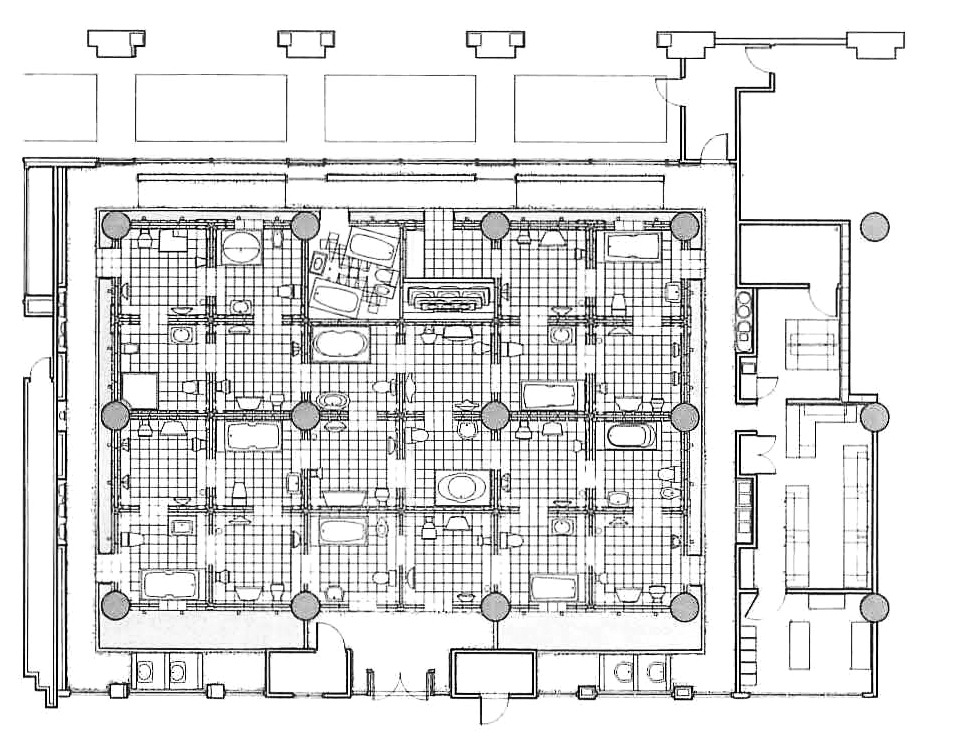

Tigerman-McCurry undertakes the design of a meta-interior: a plumbing fixture showroom for the American Standard company at the International Design Center in New York. It is a meta-interior in that it is an interior design project which seeks to spatialize the product specification process for other interior design projects. In their perhaps better-known Formica Showroom of 1986, the architects had already distinguished themselves as capable in this type of program.

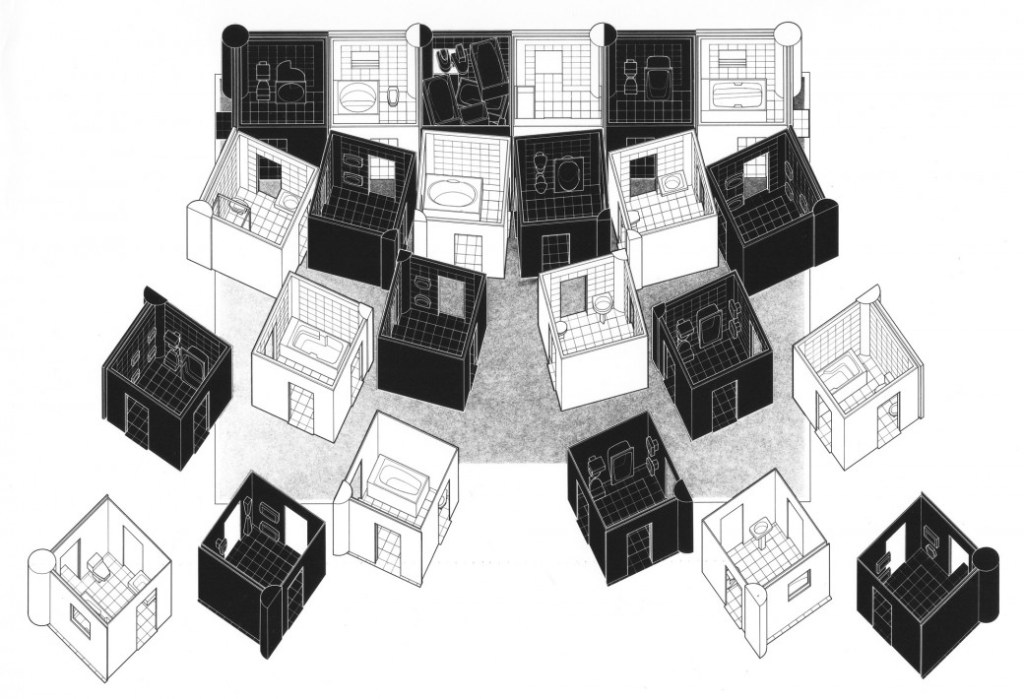

In reading the architects’ statement and descriptions from the time (including one below), it is curious that no one totally grapples with how bizarre this showroom is. They are impressed by the treatment of fixture as sculpture, yes. But, no one pauses to imagine this space as a real building: a house of twenty-four en-suite bathrooms, affording infinite variation in privacy-less excretion, hand-washing, and bathing. It’s a bathhouse that prefers the literal sum of the bathroom to the whole. It’s a showroom that only designers could love, as any normal person would be horrified. It’s a stunning appropriation of a plumbing manufacturer’s marketing budget in the service of a phantasmagoria, just for us. Tigerman calls the project a “maze that will amaze,” presumably biting his tongue that he got someone to pay for this alignment of toilets.

Tigerman-McCurry’s own Escher-esque representation of the bathroom maze. Not published in Architectural Record at the time, the drawing (from their firm website) was perhaps a post-facto project thesis.

Acknowledging that taste will play a role in future changes to the showroom design, the 10’ square steel stud grid is designed to have easily interchanged finishes and fixtures. Two cubes are reserved for rotating artistic installations.

It is unknown for how long American Standard utilized this showroom at the IDCNY, itself a rehabilitation of a pair of industrial buildings on Thomson Ave. by Gwathmey-Seigel in Queens. The buildings had ceased to be occupied by the International Design Center since as late as about 2009. And American Standard no longer has a flagship showroom.

Text excerpted in italics below from Paul M. Sachner’s review of the showroom, and images reproduced from the same issue of Architectural Record (September: Record Interiors, 1990) with photos by Timothy Hursley, unless otherwise noted:

No project so clearly exemplifies Tigerman McCurry’s longstanding effort to marry logic with whimsy than the Chicago firm’s new showroom for American Standard at the International Design Center New York. Like many manufactures, American Standard has previously exhibited its line of bathroom fixtures in elaborate model rooms, located on the ground floor of the company’s midtown Manhattan headquarters. By moving its showrooms across the East River to IDCNY, American Standard sought not to abandon totally its time-honored bathroom-suite displays, but to embellish tradition with something that would attract the attention of New York-area architects and interior designers.

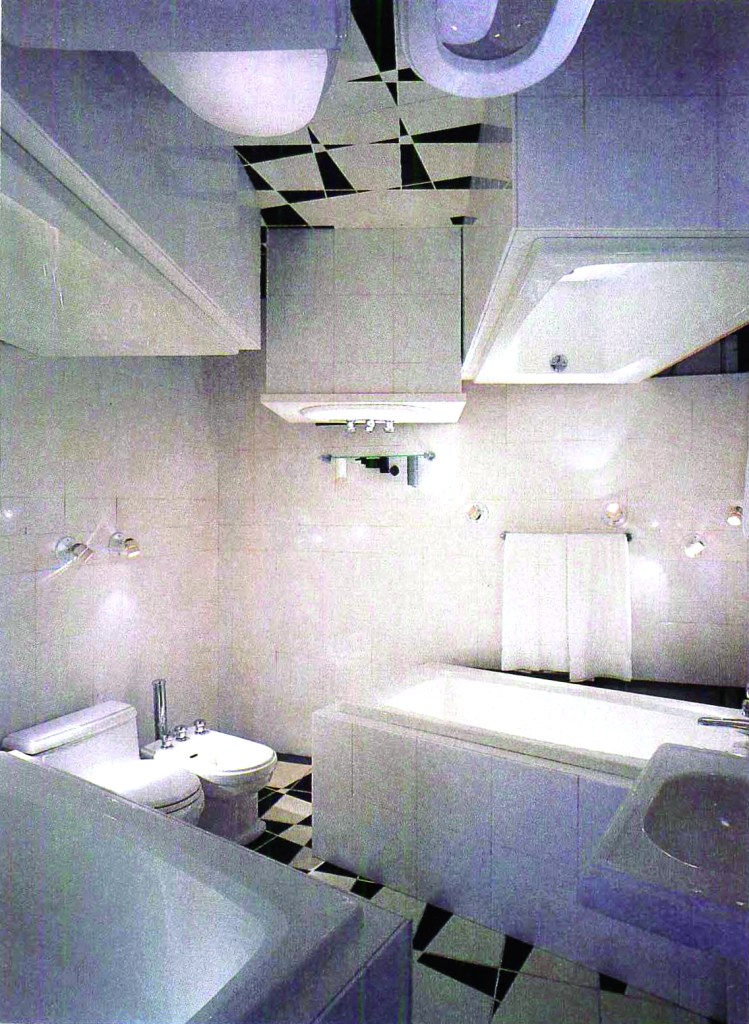

Tigerman McCurry responded by dividing up American Standard’s 6,000-square-foot space into a three-dimensional checkerboard comprising 24 10-foot cubes – alternately finished in black and white – that fit neatly into IDCNY’s existing 20-foot-on-center concrete column bays. The white cubes showcase the manufacturer’s fixture lines the old-fashioned way, in settings that mimic real bathrooms; the black cubes, by contrast, spotlight the same products with a special Tigerman McCurry twist – fixtures are mounted on the wall or, in a few cases, suspended from the ceiling. The goal, says Stanley Tigerman, is “a maze that will amaze by subsuming the architecture of the whole to the product.”

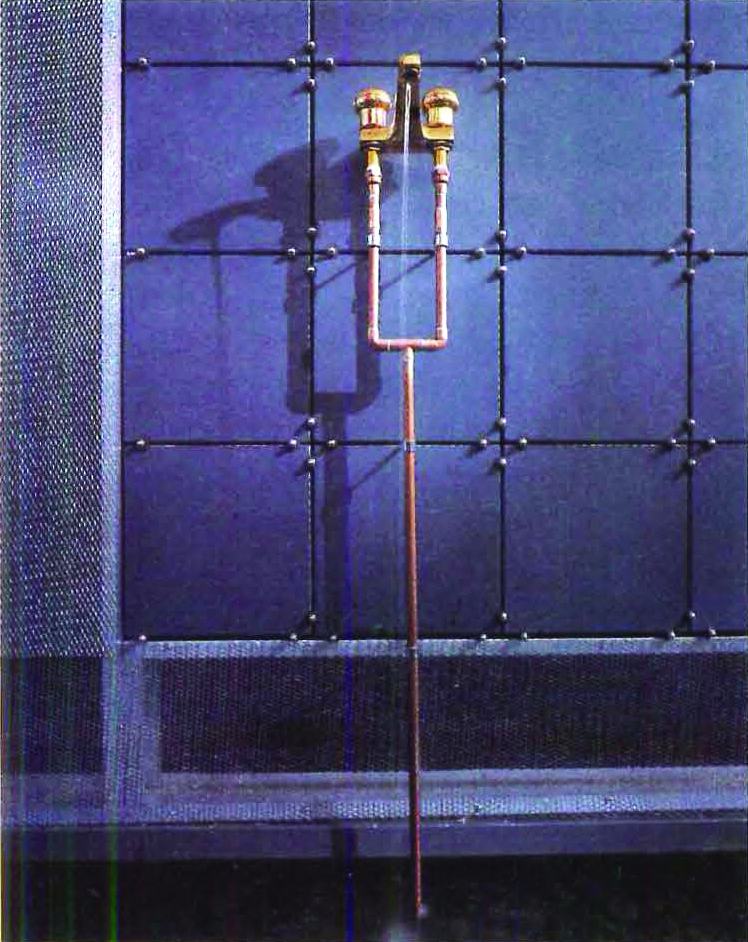

The exhibit portion of the showroom is set above raised access flooring laid over a 10-inch-deep pool. Aside from the obvious implied link between water and bathroom fittings, the pool forms the base of a perimeter fountain composed of company-made faucets installed atop exposed copper pipes. Filtered recirculating water runs continuously from the taps into the pool below, noisily animating the space.

[above] “Behind an aluminum and ceramic-tile storefront, American standard faucets sit atop copper piping attached to metal walls. The faucets run all day, filling the showroom with the sound of splashing water.” (excerpted AR)

“Two showrooms have been set aside for rotating exhibitions of invited designers’ work. In one [above, top], Stanley Tigerman hung a bathroom suite from the ceiling, skewed wildly off the axis of a similar floor-mounted group. In the second [above, below], Margaret McCurry created a fountain out of 11 sinks and 15 taps that drip softly under a canopy of forest-green bath towels.” (excerpted AR)

“Since the display is built over water, the product in the white cubes is functional (that is, each fixture flushes, sprays, pours, and whirlpools) thus animating the entire showroom. In addition, the cubes are designed such that removal and replacement is an easy task, recognizing the need for constant renewal in a facility such as this.” (excerpted from Tigerman McCurry website)

American Standard Showroom / Tigerman McCurry Architects (Stanley Tigerman & Margaret McCurry, partners-in-charge of design; Karen Lillard, project architect; David Knudson, Chris Gryder, Mark Lehmann, project team) / Client: American Standard, Inc. / Engineer: Kyong Andy Kim / Pool Consultant: Paragon-Paddock / General Contractor: Visual Communications, Inc. / Long Island City, NY / 1990