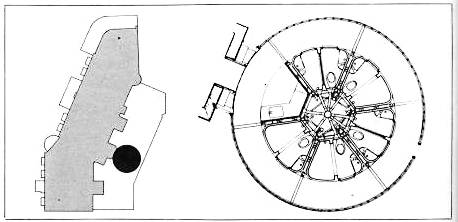

Early in Reyner Banham and the Paradoxes of High Tech (2017), Todd Gannon cites one of the founding works of the British High Tech: Nicholas Grimshaw’s (then Farrell / Grimshaw Partnership) Service Tower of the International Students’ Club of the Anglican Church in the Paddington neighborhood of London. The design of the hostel involved the conversion of several adjacent century-old terrace-houses into accommodation for 175 students. The insertion of adequate, more modern plumbing services into that masonry structure would have been impossible, so Grimshaw designed a 21’-6” diameter ‘bathroom tower’ which stands on a central steel structure apart from the existing building. Separated structurally but with a lightweight bridge connecting to corridors, the new tower could be designed with the essential proposition of providing a maximum of toilets, sinks, and showers. Instead of inserting pipes into the old house, they rise conveniently up a generous central service shaft. Grimshaw’s tower thus provides a practical method for the renovation of old buildings according to contemporary installations; it also displayed the mere provision of those installations as a perfectly confected architectural object in a way that was tantalizing to other architects.

Grimshaw / Farrell Partnership, Service Tower for Intl. Students Club, 1967, Paddington, London, UK. Site Plan and Tower Plan reproduced from Design Journal (April, 1968).

Often cited as Grimshaw’s first project, the Service Tower was completed in late 1967 and appeared in the architectural press as early as Spring of 1968. If the ‘Bathroom Tower’ projects a movement toward structural lightness and literal transparency (or at least translucency), compare it to the Tufts University Chemical Research Building (The Architects Collaborative, 1962-65) which seeks many of the same goals but through the logic of board-formed heaviness. Could an alternate reality of Brutalist High Tech (sorry to use the B-word and so many parentheticals) been born! Take that Warnecke.

Text excerpted and images reproduced in italics below from both the January 1963 and April 1965 issues of Progressive Architecture with this author’s commentary in roman. Photos by Louis Reens unless otherwise noted:

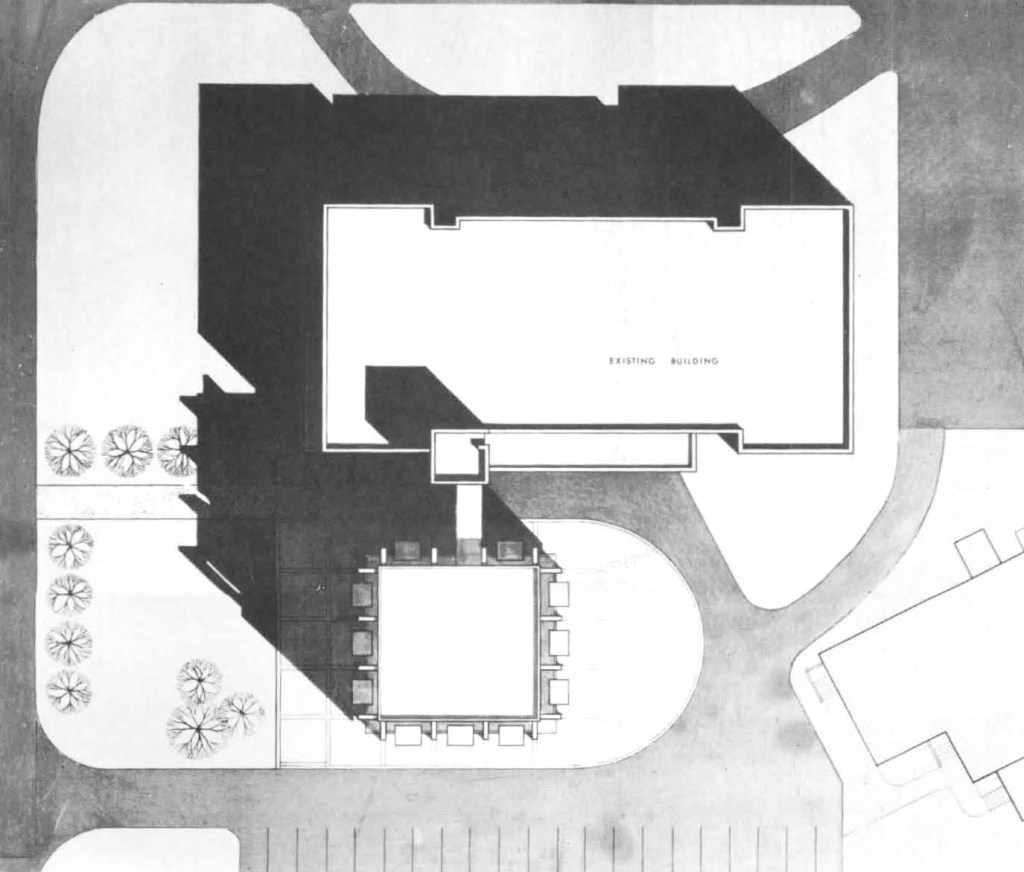

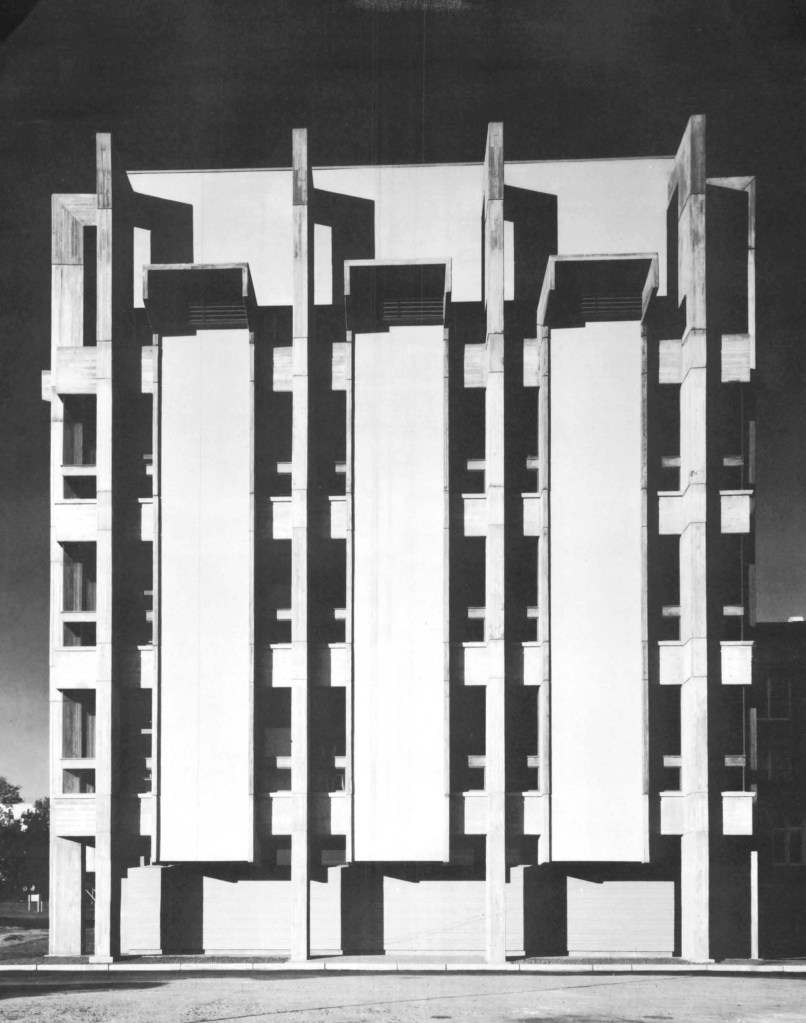

The building is actually an addition to an existing Classical Revival building. The decision to treat the new structure as a tall focal element in the campus form – rather than a mere appendage – was influenced by many factors: the desire to minimize ground coverage; the blandness of the surrounding buildings; the need for a stabilizing termination of a group of buildings running down a slope.

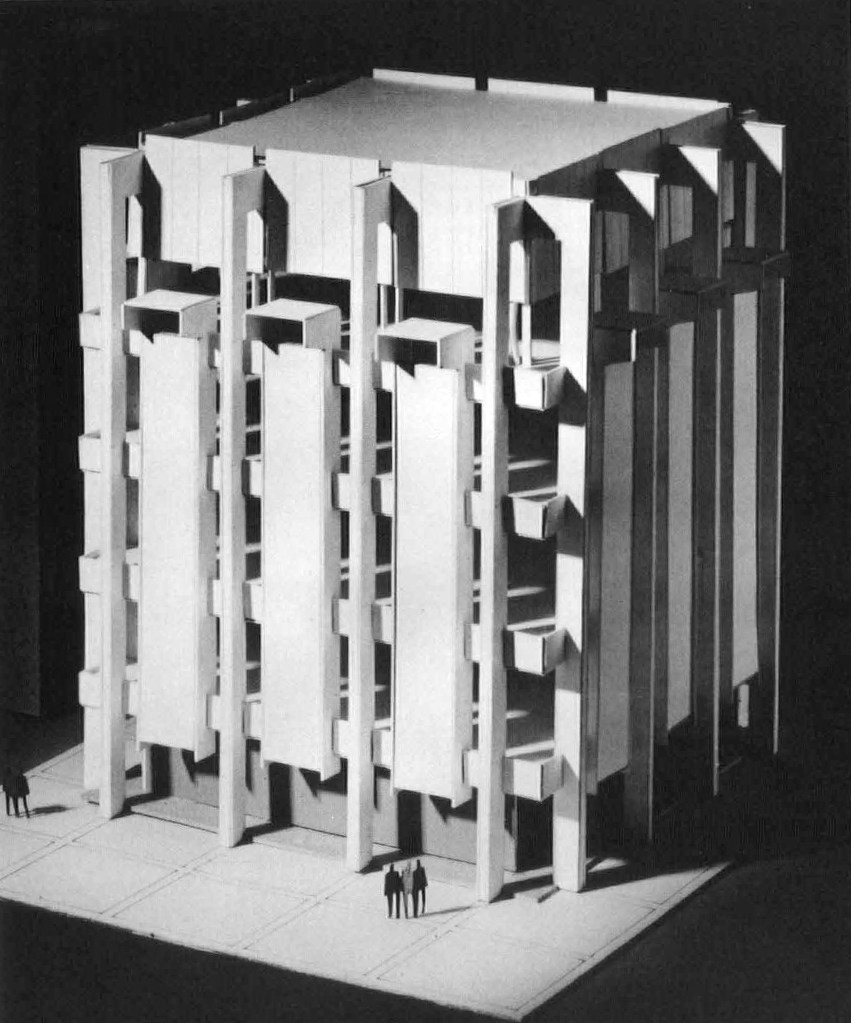

Model by Malcom Tichnor, photo by Phokian Karas, 1962

The space requirements of the program were divided readily among five floors; a base story, at the basement level of the old building, for storage and utilities; three floor of laboratories, conference rooms, and offices; one floor of library facilities. The 13’-4” floor-to-floor height of the laboratory stories was required to make the floor levels correspond to those of the existing building. The seemingly superfluous building volume involved cost very little and is of value in minimizing air pollution in the labs.

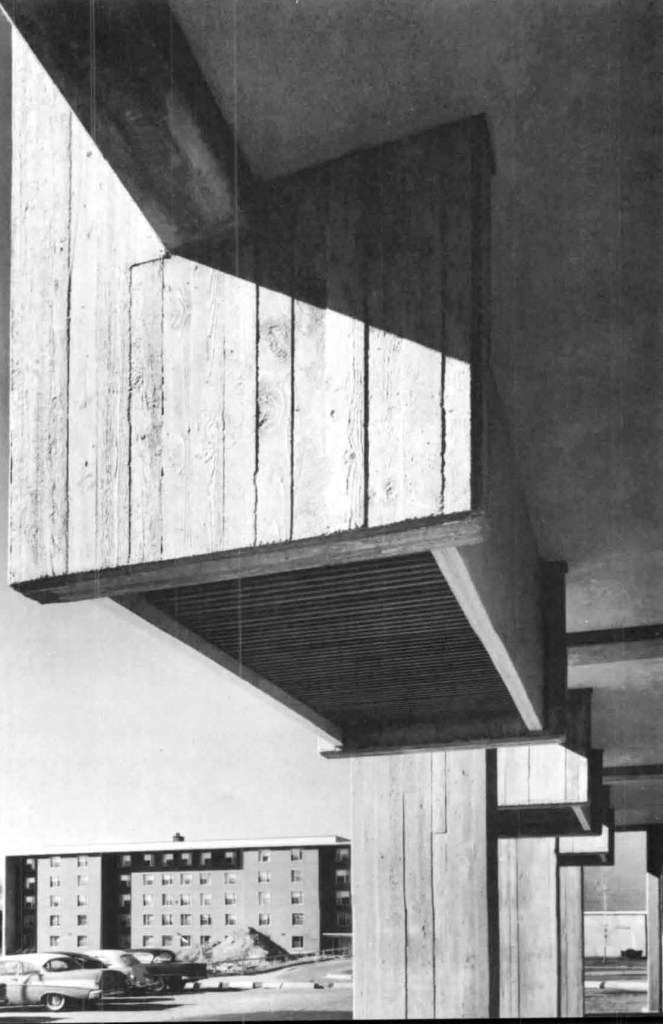

The Three distinct functional volumes of the building have been placed within an exposed structural cage of cast-in-place concrete. The four interior columns define a central circulation core, leaving the surrounding floor space entirely free of columns.

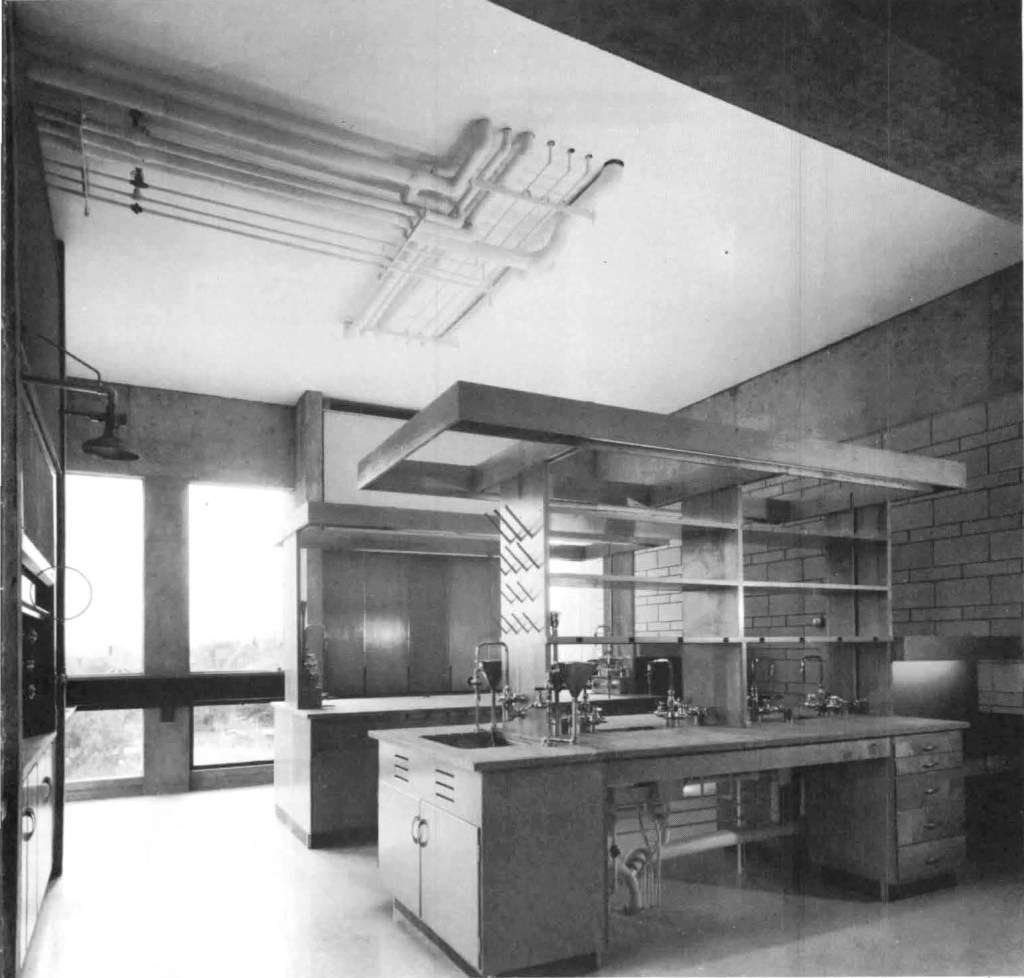

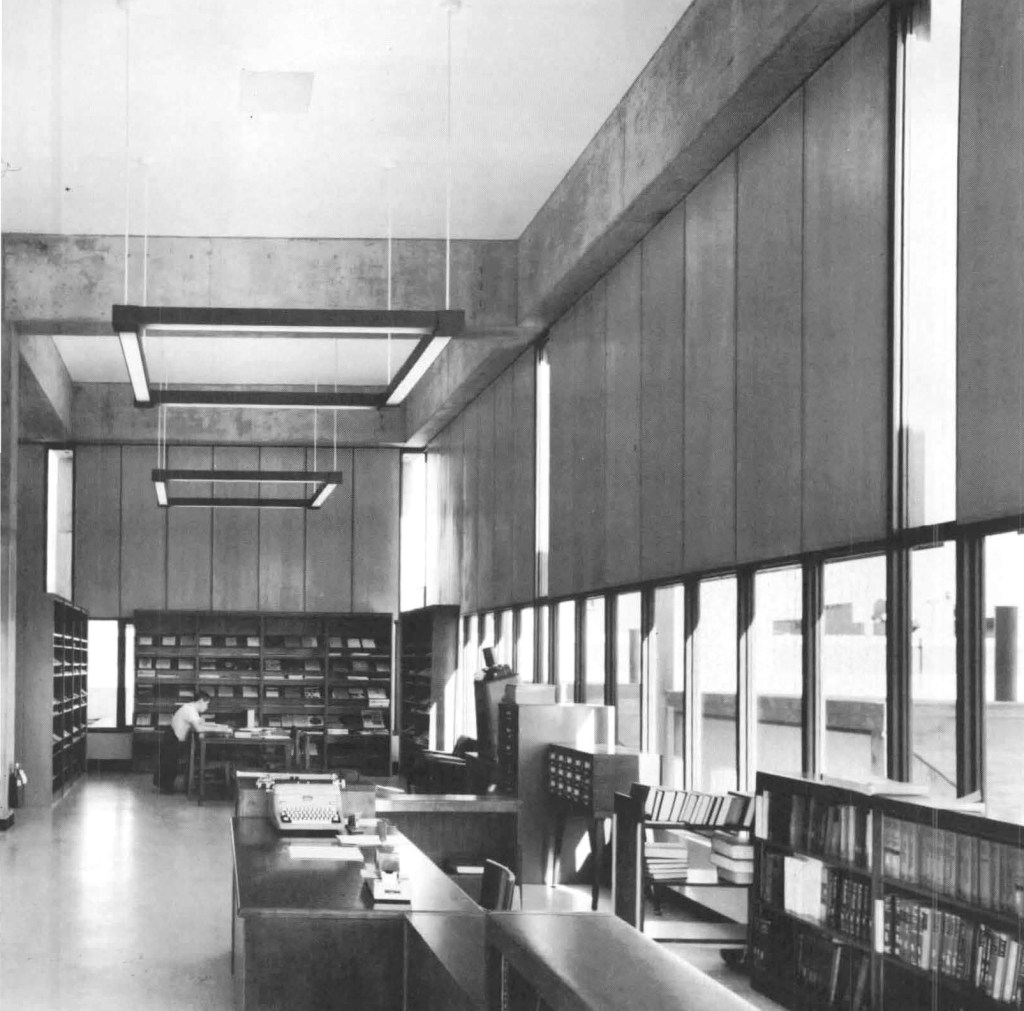

Large areas of gray glass fitted directly into the concrete structural frame giving the laboratories a pleasantly open feeling, while projecting columns and mechanical shafts eliminate most direct sunlight. Counters along the window walls, which are of wood painted with black epoxy, conceal fintube radiation. Peninsular lab benches are composed of standard elements, with modifications worked out collaboratively with the manufacturer at no extra cost: maple superstructures have electrical plug strips along shelf edges; cornice lighting is directed downward by honeycomb grilles and diffused upward to provide general room illumination; desk units have been introduced at the end of each bench. Bench tops are of alberene stone, and cabinetwork – throughout the labs – is of maple. White-painted pipes have been arranged to form attractive patterns on the white-painted plaster ceilings; only the valves are painted identifying colors. Interior walls are of 4-in. and 8-in. concrete block laid up in alternate courses, with raked joints, unpainted. Floors are coated with beige epoxy paint. Strong color is introduced in the yellow and orange painted fiber board panels above the fume hoods.

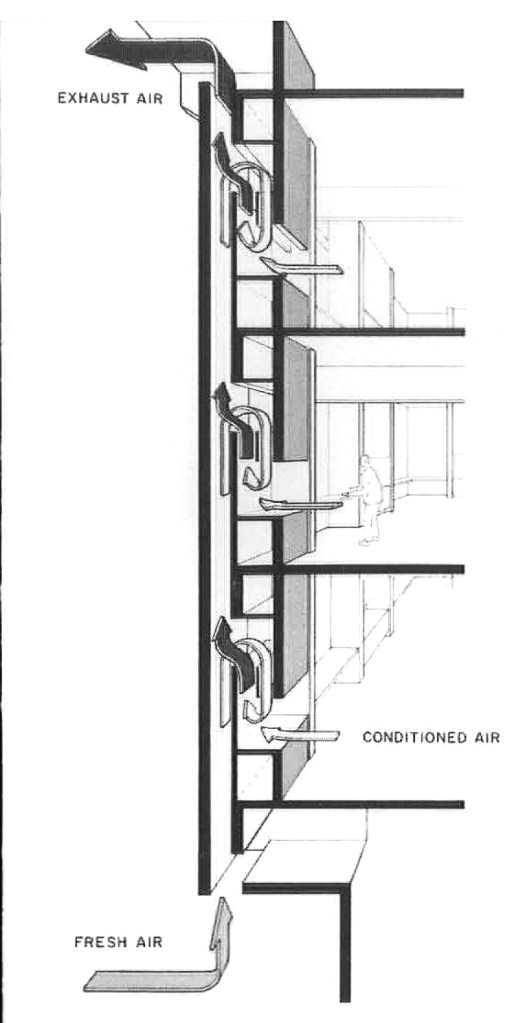

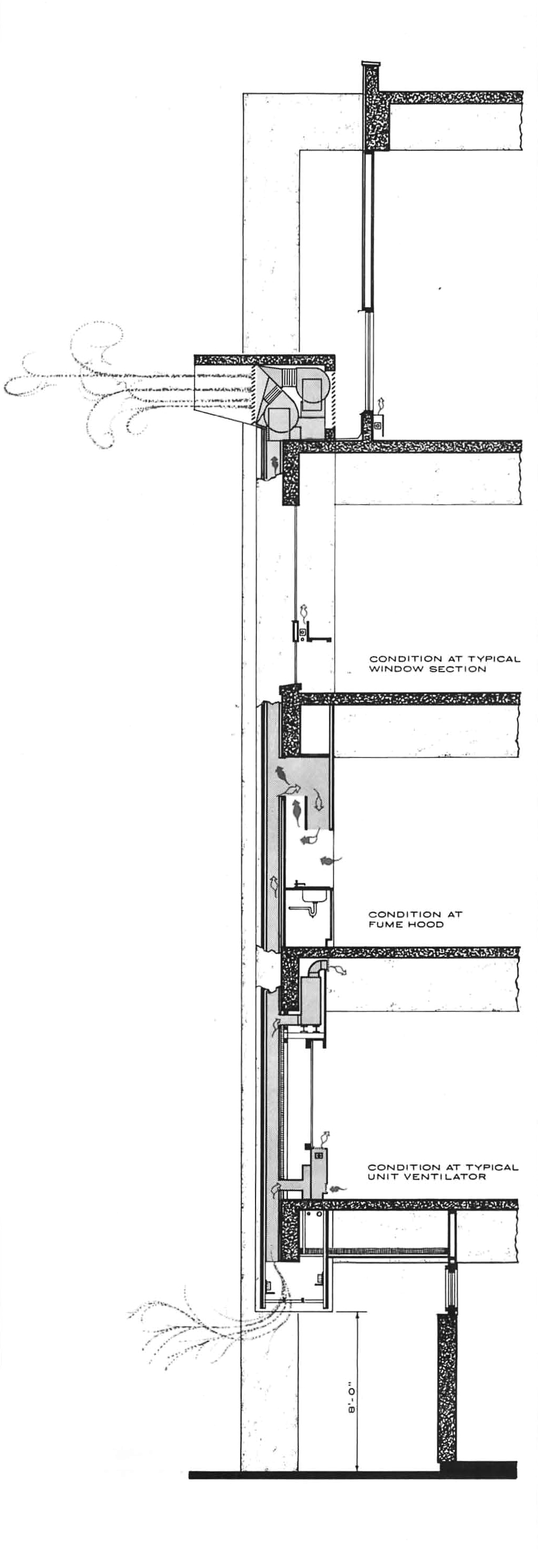

To maintain this uninterrupted space and simplify problems of air supply and exhaust, all ductwork, piping, heating and ventilating equipment, and fume hoods have been concentrated in mechanical shafts distributed around the perimeter of the building. Half of the shafts (those on two opposite sides the building) are reserved for fume hood exhaust and the other half for heating and ventilating intake. Each fume hood is paired with a unit ventilator of the same capacity so that they are switched on and off simultaneously to meet the unpredictable working schedules of the researchers […] Except for the possibility of air conditioning these offices and the library, the building will not be air-conditioned; the lower parts of all windows are operable steel sash.

Curtain walls enclosing the top-floor library are suspended from the beams overhead. They are framed in rectangular steel tubing and filled in with fixed glass, operable steel sash, and panels of maple plywood on cores of rigid insulation, surface on the exterior with epoxy stucco. The window arrangement is based partly on future plans to suspend a mezzanine over part of the room. The ceiling-high glazed slits at each column line express the nature of the wall system and indicate the expanse of the view, without introducing too much direct sunlight. The partial obstruction of the view by the projecting mechanical shafts tends to focus attention on the Boston skyline and other distant landmarks.

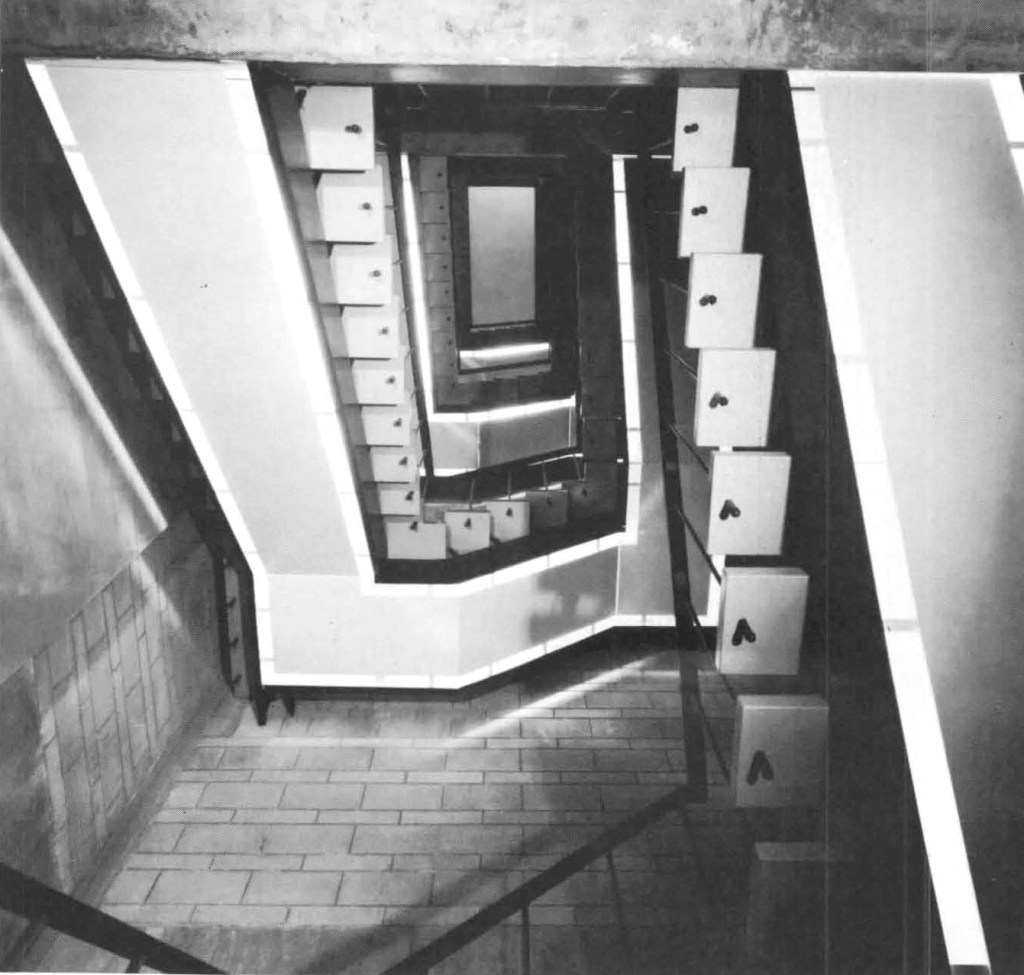

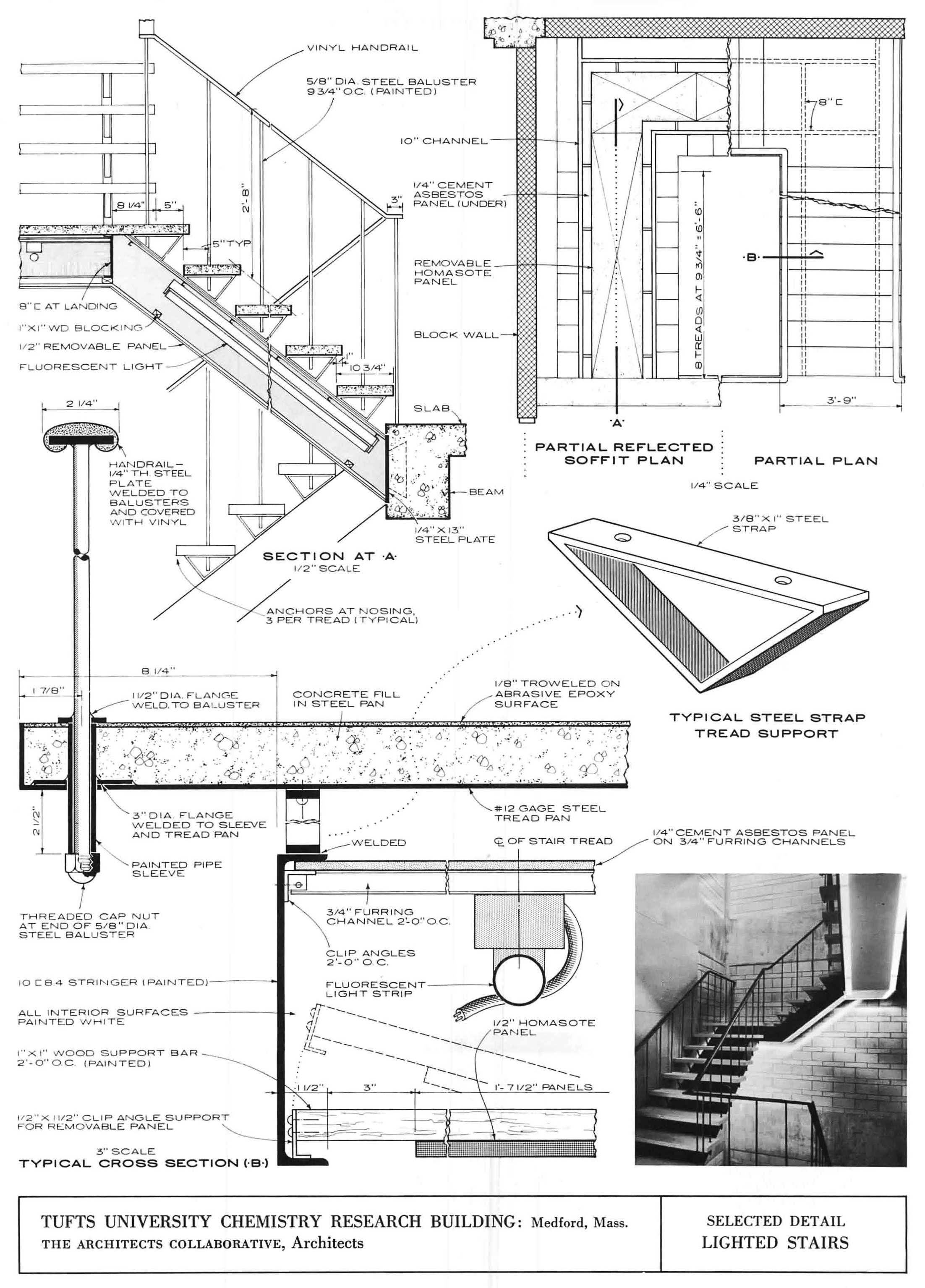

Lighting in the stairwells is build directly into the stair structure. Inexpensive fluorescent strips concealed by simple panels of fiber board provide well-distributed illumination and create a meaningful visual pattern to enliven an otherwise stark space.

The principal exterior material, aside from the exposed board-formed concrete of the structural members, is an epoxy stucco. The fixed gray glass of the laboratory floors is set directly into grooves in the concrete frame [we can’t have fun anymore]; a redwood railing separates them from the steel sash below, which rests on precast sills.

Before its construction, the building received a citation in Progressive Architecture’s annual design awards in 1963 (the theme of the issue), the jury of Aline B. Saarinen, John MacL. Johansen, Robert L. Geddes, John Skilling, and Paul Rudolph wrote:

The three major functions were found to be well expressed in architectural terms. Placement of the mechanical lines to the exterior of the building afforded important advantages. It was felt, however, that these ponderous exterior elements forced buildings “into much too big a scale for their size, their use, their site, and their occupants.

Most recent Google Streetview photo of the building, from February 2022. The additional ventilation equipment on the roof was apparently added around November of 2020, when the new vent outlets are first visible and a construction debris chute was still in place on the exterior of the building. The window frames have all been replaced from the originals. The formerly operable awning sashes below the work surfaces have been replaced with opaque spandrel panels, and now the middle-panes are operable.

Norman Fletcher (L) and Alex Cvijanovic (R), unknown photographer

Tufts University Chemistry Research Building / The Architects Collaborative (TAC) (Norman Fletcher, Partner in Charge; Alex Cvijanovic, Associate in Charge; Malcom Ticknor, Job Captain) / Medford, Massachusetts, USA / 1962-1965 / Structural Engineers: Souza & True / Mechanical Engineers: Reardon & Turner / Electrical Engineers: Verne Norman Associates / Cost: $580,648 ($27.50 / ft2) = ~$5,700,000 ($270.00 ft2) in 2023 Dollars according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI Calculator